Electrical Short Circuit

By R.W. Hurst, Editor

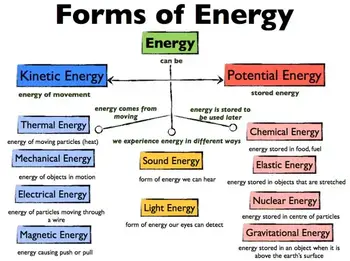

An electrical short circuit occurs when current moves through an unintended low-resistance path, creating high fault current, arc energy, and safety hazards. Proper protection, grounding, and insulation reduce risks across electrical systems.

Electrical Short Circuit Overview and Best Practices

This dangerous event can result in power outages, damaged appliances, or even fires. By understanding the types of short circuits, their causes, detection methods, and prevention strategies, we can greatly reduce the risks. When studying short circuits, it is helpful first to understand the principles of basic electricity, as the same laws of voltage, current, and resistance explain why faults occur.

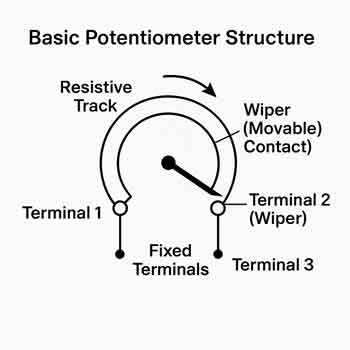

In any electrical circuit, current will always follow the path of least resistance, which is why electrical short circuit events occur when a hot wire accidentally contacts a neutral wire or grounded surface. These conditions often arise from loose connections or damaged components, as well as deteriorated or damaged wiring inside walls or appliances. Circuit breakers are designed to interrupt this sudden surge of current, but modern protection strategies increasingly rely on arc fault circuit interrupters AFCIs, which detect the signature of arcing that older devices cannot sense. AFCIs help prevent electrical shock and fire hazards by reacting quickly to irregular patterns that indicate dangerous faults developing inside the system.

Ground-related hazards require another protective device known as ground fault circuit interrupters, which monitor current flow and trip when a ground fault, an electrical short circuit, forms between a hot wire and an unintended path to earth. These faults are especially dangerous in damp locations, where the risk of shock increases dramatically. While circuit breakers respond mainly to overcurrent, GFCIs detect imbalances between the hot and neutral conductors, cutting off power before harm occurs. When combined with AFCIs, they create a layered defence against short circuits, including events caused by wiring failures, aging equipment, or installation errors.

Causes of Short Circuits

There are several reasons why an electrical short circuit may occur. Common causes include faulty appliance wiring, loose wire connections, and damaged insulation. These issues can cause current to flow through an unintended path, creating a short circuit.

Short circuits do not usually appear without warning. They often grow out of conditions that have been developing for months or years. Aging insulation may dry out or crack. A loose termination may heat up, oxidize, and eventually fail. Water can seep into an outdoor box or conduit, creating a conductive path. Rodents may chew the covering off a cable. A misplaced nail or screw can pierce a buried conductor. Inside appliances, motors, and compressors, failures can cause internal collapse of the insulation between windings.

It is also common for people to confuse different fault types. A short circuit occurs when current passes between conductors. A ground fault causes current to flow into the earth through an unintended path. An overload is different again, caused by too much current for too long, rather than a sudden collapse of resistance. Each one stresses the system in a different way, which is why codes and protection schemes treat them separately.

Detecting and Recognizing a Short

Some shorts are dramatic and obvious, but many give small signals before the protective device trips. Frequent breaker trips, dimming lights, buzzing receptacles, and a sharp smell from an outlet box all point to trouble. Melted insulation, heat discoloration, or a scorched connector indicate a fault is active or imminent.

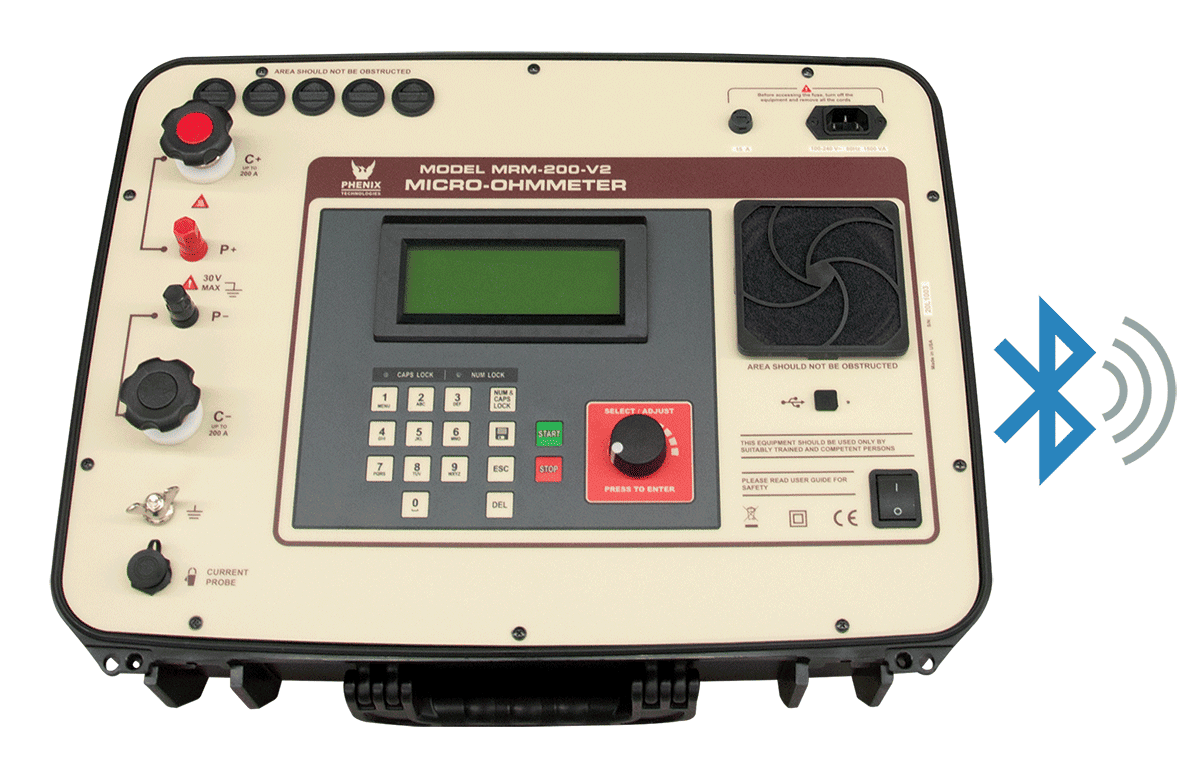

Electricians rely on several tools to trace faults. A multimeter can confirm continuity where none should exist. Clamp meters detect abnormal current. Meggers test insulation strength. Thermal imagers show hotspots that would otherwise stay hidden. In larger systems, tracers and circuit identifiers help narrow down the exact segment where conductors are touching. Ground faults are often confused with shorts, but a true electrical fault may involve multiple types of abnormal current flow.

Why an Electrical Short Circuit Is So Violent

Ohm’s Law explains the severity. When resistance collapses, current rises quickly because there's only one place for the voltage to go. That high current produces intense heat and strong magnetic forces. Conductors may warp, insulation can ignite, and equipment ratings can be exceeded in milliseconds. This is why protective devices are engineered with defined clearing times and why time-current curves are carefully chosen. A well-coordinated system limits damage and isolates the fault before it spreads. Protective devices are designed to limit current and prevent excessive electrical resistance heating that can trigger a fire.

Prevention Strategies

Most short circuits are preventable. Regular inspections of outlets, panels, and cords catch many problems early. Proper conductor sizing, secure terminations, and high-quality insulation go a long way toward fault reduction. AFCIs detect arcing patterns that ordinary breakers miss. GFCIs stop dangerous ground-fault currents. Surge protective devices shield equipment from transient spikes that can erode insulation over time. Industrial systems rely on protective relays, coordinated breakers, and redundancy to maintain continuity even when a fault occurs.

Modern codes in the United States, Canada, and international jurisdictions all require various forms of protection because decades of field experience show that these measures significantly reduce danger to people and property.

Risks and Consequences

An electrical short circuit releases a tremendous amount of energy in a short time. Wires can overheat in seconds. Flammable materials may ignite. A person who comes into contact with a faulted enclosure can be exposed to dangerous shock currents. Appliances and electronics are often destroyed when internal parts short and send fault current upstream. Industrial equipment may suffer mechanical stress, long outages, or cascading failures. This is why short-circuit protection is treated as a core part of design rather than an afterthought.

For example, a refrigerator's shorted compressor can ignite nearby insulation, while an industrial panel's short can trip upstream breakers, causing outages and costly downtime. They are one of the many dangers of electricity that electricians must guard against through the use of insulation, grounding, and protective equipment.

Repair and Response

When a short is suspected, power must be shut off immediately at the breaker or disconnect. Once the circuit is safe, visible wiring, outlets, and devices should be checked for damage. Faulted sections are replaced, not repaired. Hidden faults may require tracing tools or a licensed electrician with diagnostic experience. Short circuits are rarely suitable for improvisation; the consequences of a missed defect can be serious.

Short Circuit vs. Open Circuit

Although both conditions disrupt normal operation, they do so in opposite ways. A short circuit forces current to flow where it should not, creating a surge. An open circuit breaks continuity entirely, stopping current flow. Both conditions require correction, but the risks associated with a short are typically much higher because of the energy release.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a GFCI trip from a short?

Yes, although it is designed primarily for ground faults. Breakers or fuses must still protect against shorts between conductors.

How often should wiring be inspected?

Every five to ten years in residential settings, or sooner if signs of overheating, arcing, or repeated tripping appear.

What distinguishes a short from a ground fault?

A short is conductor-to-conductor. A ground fault is conductor-to-earth. Both are serious, and both require immediate correction.

Understanding how short circuits form, how they behave, and how to prevent them remains one of the most important aspects of safety. With proper design, regular inspection, and code-compliant protection, the vast majority of these faults can be avoided altogether.