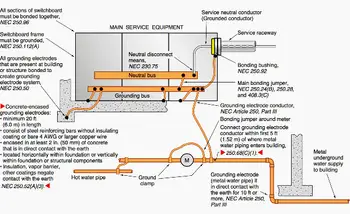

Neutral Grounding Resistor

Grounding and Bonding and The NEC - Section 250

Our customized live online or in‑person group training can be delivered to your staff at your location.

- Live Online

- 12 hours Instructor-led

- Group Training Available

Download Our OSHA 4475 Fact Sheet – Being Aware of Arc Flash Hazards

- Identify root causes of arc flash incidents and contributing conditions

- Apply prevention strategies including LOTO, PPE, and testing protocols

- Understand OSHA requirements for training and equipment maintenance

A neutral grounding resistor limits ground fault current in medium-voltage systems, reducing equipment damage, arc flash risk, and overvoltage stress while preserving system stability and fault detection capability.

Neutral Grounding Resistor in Medium-Voltage Power Systems

A neutral grounding resistor shapes ground fault behavior as part of the broader strategy that establishes system reference and safety, as explained in our formal definition of electrical grounding.

In medium-voltage industrial and utility systems, that control is often the difference between a manageable fault event and a destructive one. A neutral grounding resistor only performs as intended when integrated into grounding system architecture that organizes reference and fault control.

Unlike solidly grounded systems, where fault currents rise rapidly and violently, resistance-grounded systems use the resistor to shape the fault into something the system can tolerate. The goal is not to eliminate fault current, but to make it predictable, detectable, and survivable.

Why resistance grounding exists at all

Electrical systems do not fail politely. When insulation breaks down, current follows the laws of physics, not intentions. Without resistance in the neutral path, a ground fault can produce currents large enough to deform conductors, damage transformer windings, and create arc flash energy levels that exceed protective device capabilities.

The resistor introduces a deliberate bottleneck. It limits the fault current to a level chosen by the designer, rather than leaving it to chance. That single design choice reshapes the entire fault profile of the system, a concept explained more broadly in understanding electrical earthing.

In practice, this means:

• Lower thermal stress on equipment

• Reduced arc flash energy at the fault point

• Improved selectivity for protective relays

• Greater system stability during abnormal events

Sign Up for Electricity Forum’s Power Quality Newsletter

Stay informed with our FREE Power Quality Newsletter — get the latest news, breakthrough technologies, and expert insights, delivered straight to your inbox.

This is why a neutral grounding resistor appears so frequently in mining, petrochemical plants, pulp and paper mills, large manufacturing facilities, and medium-voltage utility networks.

Resistance Grounded Networks

In resistance-grounded networks, the neutral grounding resistor serves as the primary control point for fault current behaviour. By shaping how current returns through the system neutral during a line-to-ground event, the resistor allows protection relays to distinguish between transient disturbances and sustained faults. In high-resistance grounding (HRG) systems, this often supports continued operation with fault indication, while low-resistance grounding (LRG) favors rapid isolation once detection thresholds are reached. The difference is not philosophical; it is operational, affecting relay coordination, maintenance strategy, and risk tolerance across the entire network.

From an engineering standpoint, the selection of neutral grounding resistors is closely tied to transformer neutral earthing practice, relay sensitivity, and applicable IEEE and NEC guidance on fault detection and system stability. Ground fault detection schemes rely on predictable current magnitudes, which is exactly what resistance earthing provides when properly designed. Without that predictability, even advanced protective devices lose coordination value, and fault localization becomes uncertain rather than diagnostic.

High-resistance and low-resistance grounding in real systems

Two broad philosophies dominate the neutral grounding resistor.

HRG keeps fault current extremely low, often below 25 amps. In these systems, a single ground fault does not require immediate shutdown. Operators can locate and correct the problem while production continues, provided the system remains stable.

LRG allows higher fault currents, typically in the hundreds of amps. These systems are designed for fast fault clearing, where protective relays trip breakers quickly to isolate the faulted section. This approach is common in larger networks where equipment protection and coordination take priority.

In transformer-neutral earthing applications, the resistor establishes a predictable fault-current reference that protection relays use for selective coordination and ground-fault detection. HRG systems depend on this controlled current to support alarm-only fault response strategies, while LRG favors rapid protective isolation.

Installation and performance expectations are governed by code requirements that govern grounding behavior and fault current criteria.

What engineers actually care about when selecting an NGR

On paper, the resistor is defined by Ohm’s law. In the field, it is defined by consequences.

Designers look at:

• Line-to-neutral system voltage

• Desired ground fault current limit

• Relay sensitivity and coordination margins

• Thermal withstand time

• Physical enclosure environment

• Monitoring and alarm requirements

Fault current behavior is influenced by the path defined by the conductor that connects electrodes to the system reference.

The resistor must survive the worst fault the system can deliver, not just the one expected on a good day. IEEE and NEC guidance both emphasize fault current limitation as a core requirement for system stability in resistance-grounded networks.

Construction that matches the abuse

Neutral grounding resistors are built for punishment. Edge-wound elements, stainless or nickel-chromium alloys, and high-temperature insulation are not marketing features. They are survival requirements.

During a fault, the resistor converts electrical energy directly into heat. In poorly designed units, that heat becomes a mechanical failure. In properly designed units, it becomes a controlled, predictable rise that the enclosure and elements can absorb without permanent damage.

In mining installations, vibration and dust demand robust enclosures. In outdoor substations, weather resistance and thermal ventilation dominate design decisions. In indoor industrial plants, compact layouts and easy access for monitoring become more important.

The resistor is simple in principle, but unforgiving in execution.

Test Your Knowledge About Power Quality!

Think you know Power Quality? Take our quick, interactive quiz and test your knowledge in minutes.

- Instantly see your results and score

- Identify strengths and areas for improvement

- Challenge yourself on real-world electrical topics

Monitoring is not optional

A neutral grounding resistor that silently fails removes the entire protection philosophy of the system.

Modern installations include:

• Continuity monitoring to detect open elements

• Temperature sensing to detect overheating

• Ground fault detection relays for fault localization

• Alarm outputs tied into plant control systems

Without monitoring, a system may appear grounded while operating effectively ungrounded, creating dangerous transient overvoltages and unpredictable fault behaviour, especially in transformer-fed networks, as discussed further in transformer grounding. Neutral grounding resistors are commonly applied in systems that rely on how transformer neutrals are grounded in different system configurations.

Where neutral grounding resistors quietly earn their keep

In mining, regulations often require resistance earthing to control fault energy in confined spaces.

In utility distribution, they protect transformers and feeder equipment from destructive ground faults.

In renewable energy plants, they stabilize transformer earthing as inverter-based sources interact with the grid.

In large industrial facilities, they support selective coordination strategies that isolate faults without collapsing entire production networks.

Stable reference conditions depend on how bonding maintains continuity between conductive parts.

A note on grounding context

A neutral grounding resistor is not an earthing system by itself. It is one engineered component within a broader earthing strategy. Its effectiveness depends on how the neutral, conductors, electrodes, and protective devices work together.

In utility installations, resistor performance is influenced by electrode design principles that affect how electrodes support substation ground reference.

Maintenance that protects the investment

Periodic inspection is not about compliance paperwork. It is about verifying that the resistor still behaves the way the system design assumes it does.

Loose connections, corrosion, insulation breakdown, and blocked ventilation can all quietly degrade performance. A grounding resistor that cannot dissipate heat or maintain continuity no longer effectively limits fault current.

When it fails, it fails invisibly.

Neutral grounding resistor in one sentence

A neutral grounding resistor does not prevent faults, but it determines whether a fault becomes a controlled electrical event or an uncontrolled system failure.

Related Articles