What is Capacitance?

Capacitance is the ability of an electrical system to store electric charge when a voltage is applied across two conductive surfaces separated by an insulating material. It determines how much charge can be held for a given voltage and is measured in farads. Capacitance directly affects signal behavior, voltage stability, energy storage, and transient response in both electronic and power systems.

In practical terms, capacitance governs how circuits smooth voltage, filter noise, shape waveforms, and store short-term energy. Too little capacitance leads to instability and ripple. Too much can distort timing, introduce resonance, or stress components. Engineers do not treat capacitance as a theoretical constant, but as a design control that influences reliability, efficiency, and system behavior under real operating conditions.

Because capacitance interacts with frequency, voltage, and circuit topology, its role changes dramatically between DC storage applications and AC signal environments. Understanding that behavior is essential before selecting, sizing, or applying any capacitor in a real system.

What is Capacitance?

Capacitance (C = Q/V) expresses the amount of electric charge (Q) a system stores per unit of applied voltage (V), with the farad as the standard unit. It is not a measure of current flow but of charge-storage capability.

When voltage is applied across two conductors separated by an insulating dielectric, electric charge accumulates on each surface. That stored charge represents energy held in an electric field. The amount of charge that can be stored depends on plate area, separation distance, and dielectric material, not merely on voltage alone.

In alternating-current environments, capacitors influence circuit behavior through capacitive reactance. Rather than dissipating energy like resistance, capacitance controls how quickly voltage can change. As frequency increases, capacitive reactance decreases, allowing higher-frequency signals to pass more easily. This is why capacitance is fundamental to filtering, timing, tuning, and signal-conditioning applications in both electronic and power systems.

For a detailed breakdown of how capacitance is measured, check out the unit of capacitance to understand farads and their practical conversions.

What Determines Capacitance?

The capacitance of a capacitor is determined by its geometry and the properties of the dielectric material between the conductive plates. The unit of capacitance is the farad, which can be measured in farads. Capacitors are often rated in microfarads (μF) or picofarads (pF), depending on their size and intended use. For the basics of components that store electrical energy, see what is a capacitor to learn how these devices function and their role in circuits.

When a capacitor is connected to a voltage source, it charges, storing energy as an electrical field between its conductive plates. The amount of energy stored in a capacitor is proportional to its capacitance and the square of the voltage across it. When the voltage source is removed, the capacitor will slowly discharge, releasing the stored energy as an electrical current.

Power Quality Analysis Training

Request a Free Power Quality Training Quotation

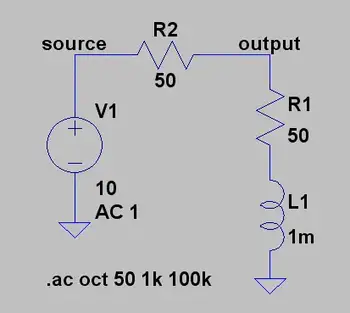

RC Circuits: The Role of Capacitance in Charging

A capacitor's charging and discharging behaviour is determined by its capacitance and the properties of the surrounding circuit. For example, in a simple circuit with a resistor and a capacitor, the capacitor will charge up rapidly when first connected to a voltage source. Still, it will then discharge slowly over time as the energy stored in the capacitor is dissipated through the resistor. The time constant of the circuit, which describes the rate at which the capacitor charges and discharges, is determined by the product of the resistance and capacitance of the circuit.

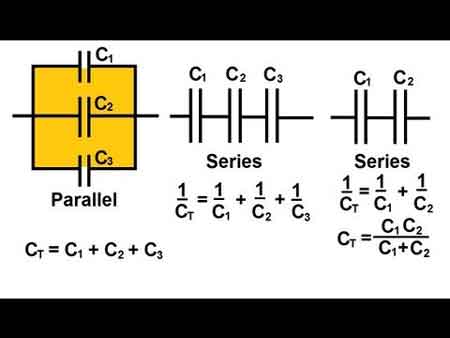

Capacitors are used in various electronic applications, from filtering noise in power supplies to storing energy in flash memory. The capacitance of a capacitor can be tuned by selecting different dielectric materials, changing the geometry of the conductive plates, or adding additional plates in parallel. To explore how capacitors behave when connected end-to-end, visit capacitance in series, which explains the reciprocal formula and voltage behavior.

Dielectric Materials and Their Effect on Capacitance

Dielectric materials are crucial to the operation of capacitors, as they serve as insulators between the conductive plates. The dielectric constant of a material describes its ability to store electrical energy and is a key parameter in determining a capacitor's capacitance. Dielectric materials can be solid, such as ceramics or plastics, or liquid, such as electrolytes.

Capacitors can store energy in various forms, from high-voltage electrical energy in power supplies to low-voltage electrical energy in portable electronic devices. The energy stored in a capacitor can provide a quick burst of power to a circuit or smooth out variations in a power supply. If you're curious about how capacitors add their values in parallel, the capacitance in parallel page illustrates how capacitances add directly, enhancing energy storage.

How Capacitance Compares to Resistance and Inductance

Resistance slows down the transfer rate of charge carriers (usually electrons) by "brute force." In this process, some energy is invariably converted from electrical form to heat. Resistance is said to consume power for this reason. Resistance is present in DC as well as in AC circuits and works the same way for either direct or alternating current. Capacitor performance depends on safe voltage levels; our page on capacitor voltage rating explains these limits in detail.

Inductance impedes the flow of AC charge carriers by temporarily storing the energy as a magnetic field. However, this energy is eventually replenished. For high-capacitance setups in electrical systems, see how banks of capacitors are configured in our capacitor bank overview.

Capacitance impedes the flow of AC charge carriers by temporarily storing the energy as an electric potential field. This energy is returned later, just as in an inductor. Capacitance is not generally necessary in pure-DC circuits. However, it can be significant in circuits where DC is pulsating rather than steady. If you're studying how capacitance affects reactive energy, visit our breakdown of the reactive power formula in electrical circuits.

Capacitance in AC Circuits and Frequency Response

Capacitance, like inductance, can appear unexpectedly or unintentionally. As with inductance, this effect becomes more evident as the ac frequency increases.

Capacitance in electric circuits is deliberately introduced by a device called a capacitor. It was discovered by the Prussian scientist Ewald Georg von Kleist in 1745 and, independently, by the Dutch physicist Pieter van Musschenbroek at about the same time, while investigating electrostatic phenomena. They discovered that electricity generated by an electrostatic machine could be stored for a period and then released. The device, which came to be known as the Leyden jar, consisted of a stoppered glass vial or jar filled with water, with a nail piercing the stopper and dipping into the water. By holding the jar in hand and touching the nail to the conductor of an electrostatic machine, they found that a shock could be obtained from the nail after disconnecting it by touching it with the free hand.

This reaction showed that some of the machine's electricity had been stored. A simple but fundamental step in the evolution of the capacitor was taken by the English astronomer John Bevis in 1747 when he replaced the water with metal foil, forming a lining on the inside surface of the glass and another covering the outside surface. The interaction of capacitance and system reactance is a key part of understanding power quality, as explained on our reactor reactance in power systems page.

A Visual Thought Experiment: Capacitance Between Metal Plates

Imagine two very large, flat sheets of metal, such as copper or aluminum, that are excellent electrical conductors. Suppose they are each the size of the state of Nebraska and are placed one on top of the other, separated by just a foot. What will happen if these two sheets of metal are connected to the terminals of a battery, as shown in Fig. 11-1?

Fig. 11-1. Two plates will become charged electrically, one positively and the other negatively.

The two plates will become charged electrically, one positively and the other negatively. You might think this would take a little while because the sheets are so big. However, this is a reasonable assumption.

If the plates were small, they would both become charged almost instantly, attaining a relative voltage equal to the battery's voltage. But because the plates are gigantic, it will take a while for the negative one to "fill up" with electrons, and it will take an equal amount of time for the other one to get electrons "sucked out." Finally, however, the voltage between the two plates will equal the battery voltage, and an electric field will exist between them.

This electric field will be small at first; the plates don't charge immediately. However, the negative and positive charges will increase over time, depending on the size of the plates and the distance between them. Figure 11-2 is a relative graph showing the intensity of the electric field between the plates as a function of time elapsed since the plates are connected to the battery terminals.

Fig. 11-2. Relative electric field intensity, as a function of time, between two metal plates connected to a voltage source.

Related Articles