Is 120V AC Dangerous?

By Frank Baker, Associate Editor

NFPA 70E Training

Our customized live online or in‑person group training can be delivered to your staff at your location.

- Live Online

- 6 hours Instructor-led

- Group Training Available

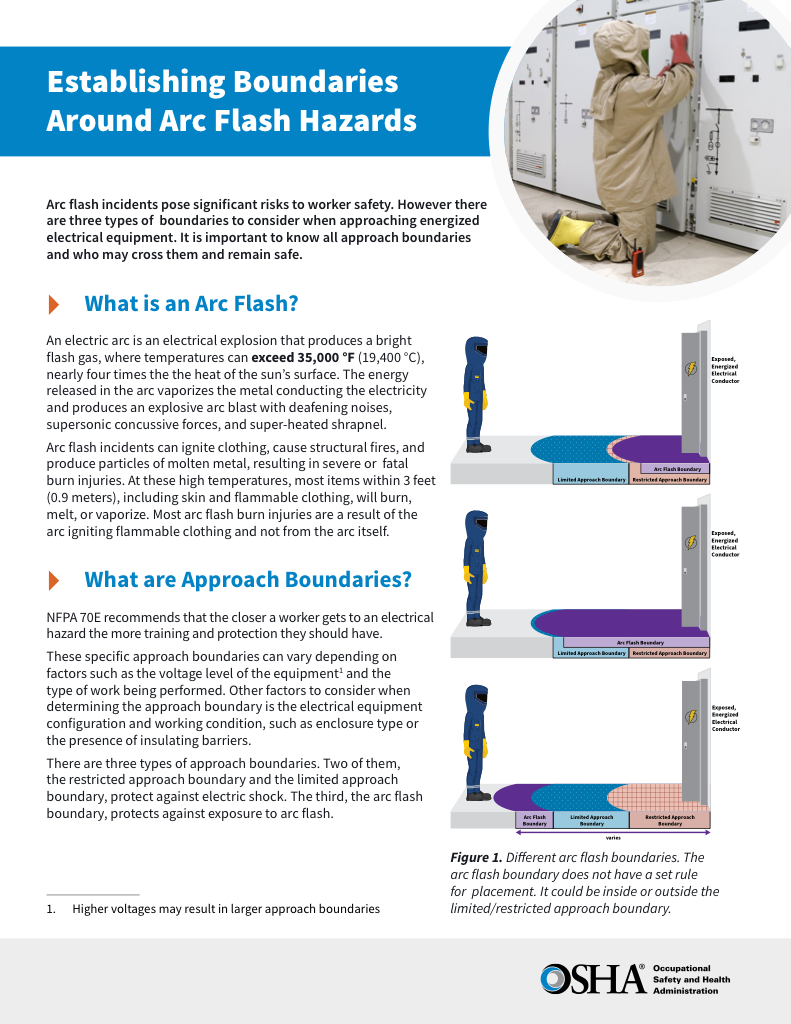

Download Our OSHA 4474 Fact Sheet – Establishing Boundaries Around Arc Flash Hazards

- Understand the difference between arc flash and electric shock boundaries

- Learn who may cross each boundary and under what conditions

- Apply voltage-based rules for safer approach distances

Is 120V AC dangerous? Household voltage can still cause electric shock, burns, or cardiac arrest, especially in wet conditions or when current crosses the chest. Understanding current flow explains why outlets deserve respect.

Because 120-volt alternating current is everywhere, in homes, offices, shops, and light industrial spaces, it is often treated as background risk rather than a real hazard. That familiarity is misleading. The voltage itself is not extreme, but the body does not experience electricity as a number on a label. It experiences current, and under the wrong conditions, 120V can push more than enough current through tissue to injure or kill.

Request a Free Training Quotation

How 120V AC Affects the Body

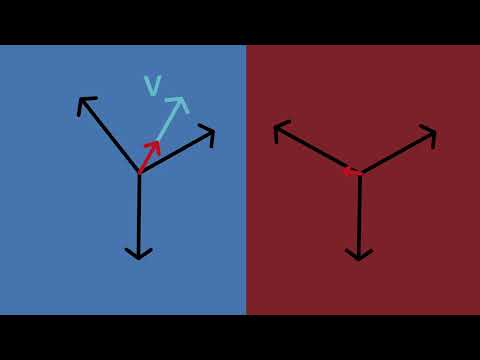

When someone contacts an energized conductor, electricity looks for a path to ground. If that path happens to pass through the hand, across the chest, and out through the feet or the opposite arm, the heart and respiratory muscles are suddenly part of the circuit. That is when a shock becomes life-threatening.

In real-world incidents, the danger is rarely dramatic or cinematic. It is a person changing a receptacle with a mislabeled breaker. A technician is working with one hand while leaning against a grounded metal surface, a homeowner standing on a damp basement floor. The voltage is ordinary. The outcome is not. Read our electricity safety article for more information about how to protect yourself from injury.

The body’s resistance changes constantly. Dry, intact skin can limit current flow, sometimes enough to turn a shock into a painful warning. Sweat, moisture, cuts, or metal jewelry can quickly remove that margin. Once resistance drops, current rises, and even a fraction of an amp can interfere with heart rhythm or lock muscles in place, preventing the person from letting go.

Sign Up for Electricity Forum’s Arc Flash Newsletter

Stay informed with our FREE Arc Flash Newsletter — get the latest news, breakthrough technologies, and expert insights, delivered straight to your inbox.

Isolation practices for 120-volt circuits exist for the same reason they do elsewhere: shock injuries tend to occur during ordinary work on systems that are left energized. See our OSHA 29 CFR 1910.147 lockout/tagout standard, which emphasizes the importance of isolating circuits, even at 120V, in preventing electrical injuries.

Why “Only 120 volts” is a Dangerous Assumption

Compared to higher voltages, 120V is less likely to cause severe arc flash injuries, but shock hazards do not scale linearly with voltage as many people assume. What matters is whether sufficient current flows through a critical path for long enough.

Higher voltages increase the likelihood of injury, but lower voltages do not mean low risk. Many fatal electrocutions in North America occur at 120V. The reason is simple: this is the voltage people interact with most often, and familiarity leads to shortcuts. Circuits are left energized. Tools are not insulated. Lockout is skipped because the task is “quick.”

This is why safety standards and experienced electricians treat any energized conductor as potentially lethal, regardless of voltage class.

Conditions that quietly raise the risk

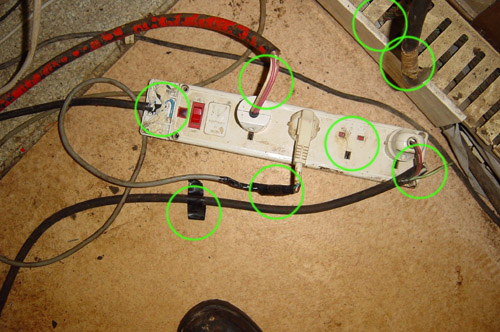

The environment often determines whether a shock becomes survivable or catastrophic. Water is the most obvious factor, but it is not the only one. Concrete floors, metal ladders, tight spaces, and awkward body positions all reduce resistance and increase exposure time.

Poor electrical grounding and damaged insulation also play a role. When grounding paths are compromised or equipment is improperly bonded, current can take unintended paths. The person holding the tool becomes part of the system. At that point, the difference between a nuisance shock and a fatal one can be as little as a few milliamps.

Experienced workers tend to recognize these conditions instinctively. They pause when something feels wrong. Less experienced individuals often do not, which is why training and procedural discipline matter even at household voltage.

Related Articles