Electricity and Magnetism - Power Explained

By Frank Baker, Associate Editor

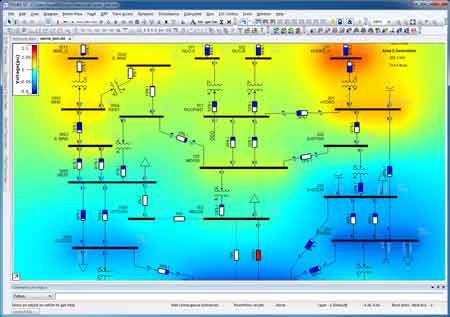

_1497200293.webp)

Electricity and magnetism shape how electric current and magnetic force interact in electromagnetic fields. These principles explain induction, energy transfer, and the operation of motors, generators, and transformers.

How Electricity and Magnetism Work

Electricity and magnetism sit at the center of how the modern world operates. We rely on them every time a motor turns, a generator produces power, or a transformer adjusts voltage. What makes these forces remarkable is not just their usefulness, but the fact that they are two expressions of the same underlying phenomenon. Understanding how they connect brings clarity to everything from simple circuits to advanced electromagnetic systems.

Electricity begins with the movement of charged particles. When charges drift through a conductor such as copper, we get an electric current, the driving force behind lighting, appliances, communications equipment, electrical machinery, and nearly everything that runs on energy. Current is an organized motion, directed through wires, much like water flows through a channel. When an electric current flows, it produces a magnetic field, a concept closely tied to Faraday's Law of Induction, which underpins much of modern electrical engineering.

Engineers of electricity and magnetism study how voltage pushes charges forward and how resistance slows their movement, but the real insight comes when current does more than travel from point to point. As soon as charges move, they create a surrounding influence that affects the space around the conductor. This concept is essential for understanding power distribution, load behaviour, and the principles of what an electric load is and how current interacts with the electromagnetic environment of a circuit.

Electricity – What is it?

Electricity begins with the movement of charged particles. When charges drift through a conductor such as copper, an electric current is generated, powering lighting, motors, tools, and communications equipment. The flow is shaped by voltage, resistance, and the circuit's design, but it becomes even more interesting when magnetic effects are introduced.

As charges move, they shape the space around the wire, creating patterns and forces that extend outward. This behavior is fundamental to how transformers operate, how motors generate torque, and how electrical systems transfer energy from one point to another.

Magnetism - What is it?

Electricity and Magnetism are easier to picture because we have all interacted with magnets. A magnet can pull or push another object without touching it, and that invisible influence extends through the region around it. That region is called the magnetic field. Although magnets feel familiar, their behavior is rooted in the motion and arrangement of electric charges, especially electrons inside materials.

A coil of wire wrapped around a core demonstrates how a moving charge creates a magnetic field that interacts with its surroundings, much like the field around a bar magnet. When current flows, it also creates an electric influence that can be visualized by sprinkling iron filings nearby, which align themselves to reveal the structure and direction of the combined fields.

Two magnets attract or repel depending on how their poles are aligned, but the field they produce is continuous, stretching outward and shaping how nearby materials respond. To explore how field strength is measured and applied, see our magnetic induction basics, which explain concepts such as flux density and the Tesla. To understand magnetic field strength and units, our magnetic induction basics in induction page discusses flux and Teslas.

What is the relationship between electricity and magnetism?

For centuries, electricity and magnetism were treated as unrelated subjects. The breakthrough came during the 1800s when scientists began noticing that electrical activity could influence magnetic readings. In 1820, Hans Christian Ørsted made the key observation: whenever a current passed through a nearby wire, the needle of a compass shifted. This simple experiment revealed that current generates a magnetic effect.

The relationship works in the opposite direction as well. When the magnetic environment around a conductor changes, it can push on charges, creating a current. Engineers rely on this principle of induction when designing transformers, alternators, and countless power-system components. Maxwell later showed mathematically that the two forces are intertwined parts of a single electromagnetic framework.

Static electricity offers a simple way to see electrical forces at work. Rubbing two materials together can leave each with an imbalance of charge. The familiar clinging of plastic wrap is one result. In other situations, the imbalance leads to repulsion instead of attraction, a reminder that the sign of the charge matters. To explore these behaviours more formally, visit the page on what is static electricity.

Electric Fields

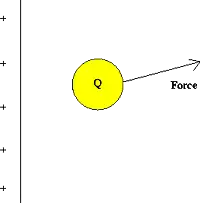

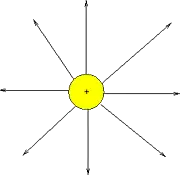

To describe how charges influence their surroundings, physicists introduced the idea of the electric field. Instead of focusing solely on one charge pushing another, the field model lets us picture how each point in space has its own direction and intensity determined by the nearby distribution of charge.

Fig. 1 Test charge in the presence of a fixed charge distribution

This charge will experience a force due to the presence of the other charges. One defines the electric field of the charge distribution as:

A test charge placed at any point experiences a force governed by the local field. Because charges differ in magnitude and can be arranged in countless geometries, the electric field varies from point to point. Its direction is defined by the force acting on a positive charge placed in that region, a convention that provides consistency across diagrams and analyses.

By convention, the direction of the electric field at a point is the direction of the force on a positive test charge placed at that point. An example of the electric field due to a positive point charge is given below.

Fig. 2: Electric field lines of a positive charge

Power and Magnetic Fields

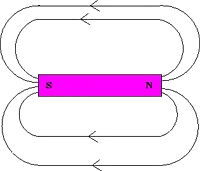

Magnetic fields are used in much the same descriptive way as electric fields. A bar magnet creates a pattern of lines that curve from its north pole to its south pole. Those lines represent the orientation that a compass needle would take if placed at any location around the magnet.

Fig. 3: Magnetic field lines of a bar magnet

Unlike electric charge, which can exist as isolated positive or negative quantities, magnetic poles always appear in pairs. Cutting a magnet in half does not isolate a north or a south pole. Each piece becomes a new magnet with its own pair of poles, a fact tied to the atomic origins of magnetism.

Magnetic Forces On Moving Charges

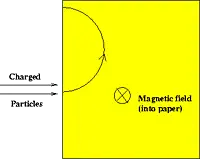

When a charged particle moves through a magnetic field, it experiences a sideways force. This force changes the particle’s direction but not its speed. The motion resembles a curve or spiral, depending on the particle’s initial velocity. Laboratories exploit this principle to steer ion beams, identify chemical elements, and generate high-energy collisions. A mass spectrometer is one such device, using predictable bending patterns to identify unknown particles.

Figure 4: Mass spectrometer

In this device, a beam of charged particles (ions) enters a region of a magnetic field, where they experience a force that bends them into a circular path. The amount of bending depends on the mass (and charge) of the particle, and by measuring this amount, one can infer the type of particle that is present by comparing it to the bending of known elements.

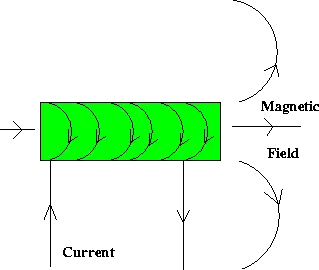

Magnet Power From Electric Power

Once Ørsted’s discovery emerged, it became clear that a simple loop of wire carrying current could act like a magnet. Wind that wire into a coil, increase the current, and the magnetic effect strengthens dramatically. This arrangement forms the basis of the electromagnet, a tool used in machinery, relays, lifting equipment, and many industrial systems.

Figure 5: Electromagnet

The same idea applies at the atomic level. Electrons orbiting a nucleus behave like tiny current loops, giving rise to magnetic properties in certain materials. When these effects align across many atoms, we get the familiar behavior of magnetic materials.

Maxwell’s equations later unified all these observations, showing that electricity and magnetism are woven together in a single framework that also predicts electromagnetic waves, the basis for radio communication, power transfer, and modern electronics.

Related Articles

_1497174704.webp)