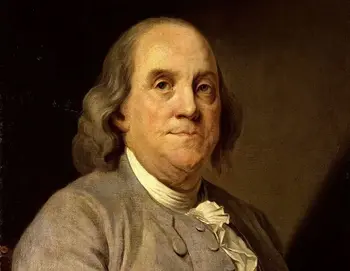

Did Ben Franklin Really Discover Electricity?

By Howard Williams, Associate Editor

Ben Franklin discovered electricity, explaining how Franklin’s kite experiment, lightning research, Leyden jar studies, and grounding insights shaped early electrical science and influenced modern concepts of charge, conductors, and circuit safety.

Why Understanding Ben Franklin's Discovery of Electricity Is Important

Ben Franklin’s place in the story of electricity is often reduced to a simple image, a kite rising into a storm. The reality is more interesting and far more important. His work unfolded within a long progression of studies on static charge, conductors, Leyden jars, and atmospheric electricity that were already underway in Europe. Franklin’s originality came from the way he connected ideas, asked questions others had not asked, and pushed his experiments toward practical consequences.

These ideas also foreshadow links between charge, fields, and induction outlined in foundational electricity and magnetism resources that situate Franklin's work within later theory.

Historians remind us that Franklin did not “discover electricity,” because the existence of electrical phenomena was already known. What he did was recognize patterns that others missed and develop a language to explain them. His letters to Peter Collinson, beginning in 1747, reveal a mind turning raw observation into structured understanding. In these early notes Franklin described how pointed conductors could attract or release electrical charge, a phenomenon that had not been fully appreciated. He also introduced the terminology of “positive” and “negative” electricity, framing charge as something that could be transferred, balanced, and measured.

Practical consequences of these insights are summarized in an overview of Franklin's contributions to electricity that explains the lightning rod's impact on public safety.

The Leyden jar was the central puzzle of that era. Philosophers knew it stored charge, yet its behavior was poorly understood. Franklin showed that the jar did not accumulate extra electricity but redistributed it, leaving one side depleted and the other enriched. When the two sides were connected, the imbalance resolved itself in a single discharge. This explanation advanced electrical research by grounding the phenomenon in logic rather than mystery. He later demonstrated that the charge resided in the glass, not the metal coatings, a conclusion he supported through simple, elegant experiments that could be repeated.

This experiment is often positioned on timelines such as a chronology of electricity's history that maps how one breakthrough enabled the next.

By 1749, Franklin had begun to apply these ideas to the natural world. Lightning, he proposed, was an electrical discharge on a massive scale. This was a bold claim at a time when thunder and lightning were regarded with superstition and fear. His notion that the atmosphere behaved like a large electrical system opened the door to practical safety measures. If lightning behaved like ordinary electrical charge, then conductors could redirect it harmlessly into the ground. This became the foundation of the lightning rod, one of the first devices in history to turn scientific theory into widespread public protection.

The famous kite experiment of 1752 was not an act of bravado but a calculated method for testing a theory without a tall tower. Using a silk-covered frame, a pointed wire, and a hemp string transitioning to silk, Franklin created a pathway to collect charge from a passing thundercloud. As the fibres lifted, he extended his knuckle toward the key and drew a spark. In that moment, he confirmed that atmospheric electricity behaved like the charge found in laboratory experiments. The test also validated the logic behind his proposed lightning rod.

News of his findings spread quickly. European scientists, including Buffon, Dalibard, and De Lor, repeated the experiments using tall structures, drawing sparks from the sky and confirming the same results. Their replications gave Franklin’s ideas international credibility. The tragic death of Professor Richmann in Russia while attempting a similar experiment underscored the danger of this work and reinforced the importance of Franklin’s safer, grounded designs.

The broader legacy of Franklin’s electrical research is not a single experiment but a shift in thinking. He helped move the study of electricity from curiosity to discipline, from spectacle to explanation. His insights foreshadowed later theories of electric fields, induction, and charge distribution, which would shape the work of Faraday, Maxwell, and the broader landscape of electrical engineering. They also led directly to the development of practical safety systems that continue to protect buildings and equipment today.

Such international replication also illuminates the distinction between discovery and invention discussed in analyses of who invented electricity that parse credit across different achievements.

Franklin’s contribution rests on three enduring achievements. He clarified how charge behaves. He showed that natural and artificial electricity follow the same rules. And he applied scientific insight to real human needs by inventing the lightning rod. These combined efforts place him firmly in the lineage of thinkers who transformed electricity from a mystery into a field of knowledge.

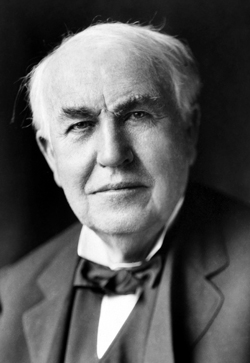

Later innovators, including Edison, would translate this scientific understanding into widespread applications described in accounts of Thomas Edison's work with electricity that trace the path from lab to industry.