Power System Analysis and Design

By R.W. Hurst, Editor

Short Circuit Study & Protective Device Coordination

Our customized live online or in‑person group training can be delivered to your staff at your location.

- Live Online

- 12 hours Instructor-led

- Group Training Available

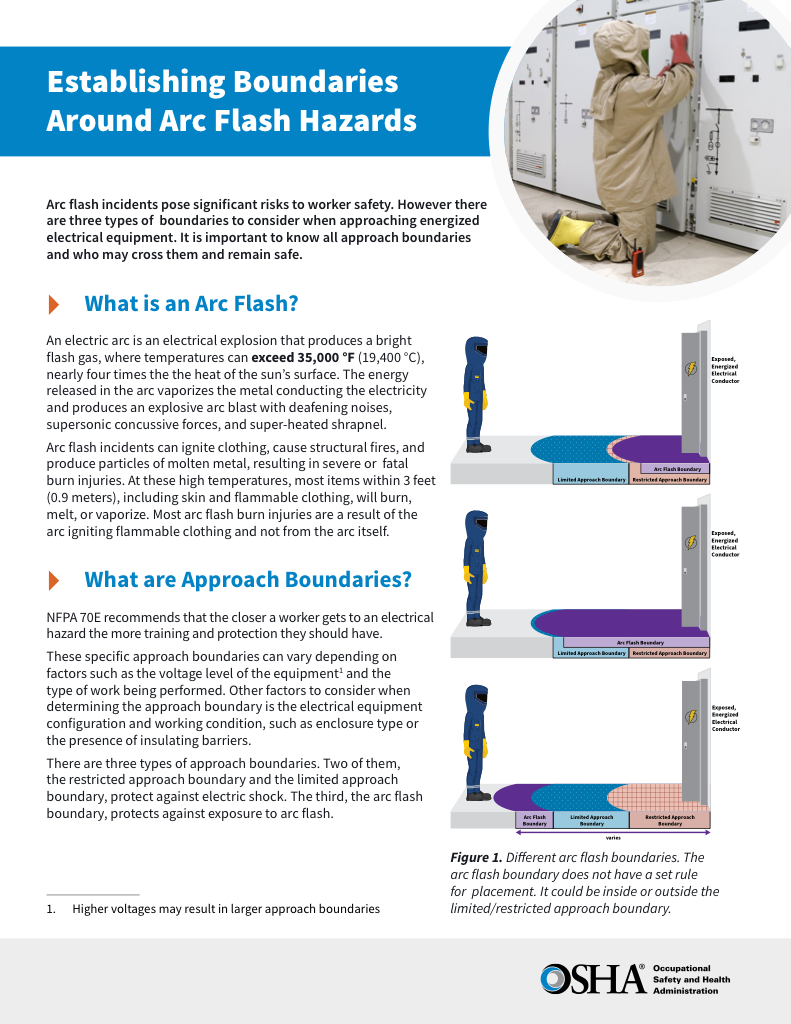

Download Our OSHA 4474 Fact Sheet – Establishing Boundaries Around Arc Flash Hazards

- Understand the difference between arc flash and electric shock boundaries

- Learn who may cross each boundary and under what conditions

- Apply voltage-based rules for safer approach distances

Power system analysis and design is the engineering discipline that converts analytical results into defensible decisions about protection, stability, equipment selection, and system configuration in electrical networks. It determines how transmission and distribution systems are structured, so they operate reliably under normal conditions and remain controlled during disturbances.

Design decisions rely on analytical boundaries that define voltage margins, fault limits, stability behavior, and protection requirements. Without those boundaries, system design becomes assumption-based rather than defensible.

Power system analysis establishes analytical boundaries, and design applies them in practice, using analysis results to guide protection, stability, and equipment decisions.

Why Power System Analysis and Design Matters

Modern power networks must support rising demand, renewable integration, and increasingly complex operating conditions. Engineers are no longer designing static systems. They are shaping networks that must respond predictably to disturbances, adapt to variable generation, and maintain performance under uncertainty.

Within the broader field of power system engineering, design decisions are only as reliable as the analytical insights that underpin them. Voltage margins, fault levels, stability limits, and protection constraints all impose boundaries that design must respect.

Design Pillars Driven by Analysis

Applied design relies on three analytical pillars.

-

Steady-state analysis defines how voltage, current, and power are distributed under normal operating conditions. Designers use these results to determine conductor sizing, transformer ratings, voltage control strategies, and reinforcement priorities. Advanced methods in load flow analysis allow engineers to refine voltage profiles and transfer limits before construction or modification begins.

-

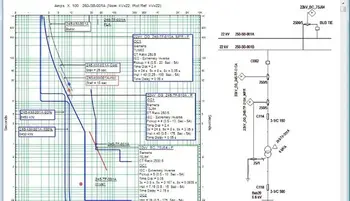

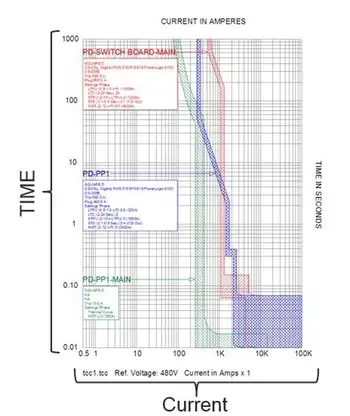

Fault analysis establishes the electrical stress that equipment must withstand. Short-circuit current levels dictate breaker ratings, bus strength, and protection coordination. Without accurate fault results, design margins become assumptions rather than engineering conclusions.

-

Stability analysis governs whether a system can recover after a disturbance. Design choices for control systems, inertia support, damping, and topology are directly guided by the stability boundaries identified in analytical studies.

FREE EF Electrical Training Catalog

Download our FREE Electrical Training Catalog and explore a full range of expert-led electrical training courses.

- Live online and in-person courses available

- Real-time instruction with Q&A from industry experts

- Flexible scheduling for your convenience

System Components in Design Context

Each power system analysis and design component is evaluated through analytical constraints.

- Generation sources influence inertia, voltage regulation, and fault behavior.

- Transmission networks balance thermal, stability, and transfer limits.

- Distribution systems must support voltage control, isolation, and expansion.

- Loads affect harmonic behavior, reactive demand, and dynamic response.

- Protection systems are configured using analytical fault envelopes.

- Control systems are tuned using stability and dynamic performance results.

No component is designed in isolation. Each exists within a system whose behavior has already been analytically characterized.

Principles Guiding Design Decisions

Design engineers rely on circuit laws, normalized per-unit representation, and power equations to translate analytical output into hardware decisions. However, effective design emerges not from equations alone, but from understanding how analytical limits constrain practical implementation.

Voltage regulation strategies must account for both steady-state and dynamic behavior. Protection schemes must operate within fault envelopes. Control architectures must remain inside stability margins. Design is the discipline of fitting physical solutions inside analytical boundaries.

From Analysis to Design Execution

Once analytical studies are complete, the power system analysis and design convert results into specifications.

- Bus ratings are based on fault and thermal limits.

- Relay settings follow coordination envelopes.

- Transformer impedance choices influence fault and voltage behavior.

- Line configurations affect power transfer and stability margins.

This transition from analytical insight to physical structure defines the practice of power system analysis and design engineering.

Designing for Stability and Reliability

Reliable networks are created by disciplined alignment between analysis and structure.

- Redundant paths must remain stable under contingency.

- Protection must operate within analytical fault limits.

- Control systems must respond within stability margins.

Dynamic stability analysis, therefore, becomes a design validation tool rather than merely a study exercise.

Modern Design Challenges

Distributed energy resources, electric vehicles, and power electronics are reshaping grid behavior. Traditional assumptions about inertia, fault current, and voltage control no longer apply universally. Design practice must now account for inverter-based generation, bidirectional power flow, and decentralized control.

Power system analysis and design has become an iterative discipline in which analytical results and design decisions continuously refine one another.

Advanced Technology Influence

Artificial intelligence, machine learning, and data analytics increasingly support design optimization and predictive maintenance. These tools do not replace analytical discipline. They operate within analytical frameworks defined by power system behavior.

High-voltage direct current transmission further extends design complexity by introducing new control dynamics and interaction challenges that must be evaluated analytically before being trusted operationally.

Related Articles