Transformer Cooling Explained

By Frank Baker, Technical Editor

Transformer Maintenance Training - Testing and Diagnostics

Our customized live online or in‑person group training can be delivered to your staff at your location.

- Live Online

- 12 hours Instructor-led

- Group Training Available

Download Our OSHA FS3529 Fact Sheet – Lockout/Tagout Safety Procedures

- Learn how to disable machines and isolate energy sources safely

- Follow OSHA guidelines for developing energy control programs

- Protect workers with proper lockout devices and annual inspections

Transformer cooling controls heat in windings and cores using oil circulation, radiators, fans, and pumps. Proper thermal management slows insulation aging, stabilizes efficiency, and supports reliable operation across ONAN, ONAF, and OFAF designs.

Transformer cooling controls heat produced by core and winding losses, protecting insulation life, efficiency, and mechanical stability under real operating loads. Effective thermal management reduces aging stress, stabilizes electrical performance, and preserves long-term transformer reliability.

For readers seeking a broader operational context, this thermal behavior fits within the overall framework of how power transformers manage electrical and mechanical losses over decades of service.

Heat is an unavoidable byproduct of electromagnetic conversion. Even in efficient designs, losses accumulate as the temperature rises. In smaller units, the effect is modest. In high-capacity transformers, the same percentage of loss becomes a dominant life-limiting factor. Cooling is therefore not a supporting feature; it is a governing condition.

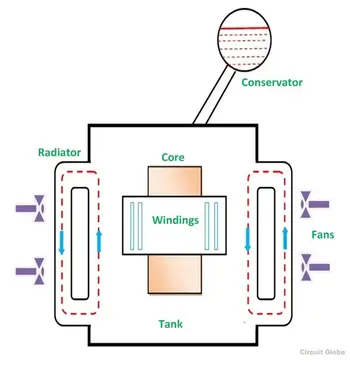

Transformer Cooling begins with circulation

In liquid-filled transformers, oil serves two roles at once. It insulates electrical components and removes heat from active components. As windings and cores warm, oil density changes, and natural circulation begins. Cooler oil descends while warmer oil rises toward radiators or heat exchangers, creating a continuous thermal loop.

This circulation path is closely tied to the geometry of the transformer core and winding structure, which determines how efficiently heat can escape high-loss regions.

When loads increase or ambient temperatures rise, natural circulation alone may no longer maintain acceptable operating limits. Fans and pumps are then introduced to accelerate heat transfer. This progression from natural to forced cooling reflects how closely thermal control follows operating demand.

Electricity Today T&D Magazine Subscribe for FREE

- Timely insights from industry experts

- Practical solutions T&D engineers

- Free access to every issue

Modern transformer cooling methods rely on a carefully balanced cooling system that may combine natural convection with various forms of external cooling depending on load and installation limits. In oil immersed designs, heat may be removed through oil natural air forced circulation in lighter duty units, while heavier equipment often operates as ONAF cooled or oil forced water forced systems when thermal margins tighten.

Some installations also use forced-air or forced-water cooling to stabilize temperatures during peak demand, while oil-forced-water arrangements remain common in large substations. Regardless of configuration, each cooling approach reflects how transformer cooling methods adapt to operating stress rather than following a single universal design.

Why transformer cooling determines insulation life

Insulation does not fail suddenly. It weakens gradually as the temperature accelerates chemical aging. Each sustained rise in operating temperature disproportionately shortens insulation life. Cooling, therefore, determines not only whether a transformer survives today, but how long it remains structurally viable.

This aging process directly affects the transformer’s insulation system, which loses mechanical strength long before electrical breakdown becomes visible.

This relationship explains why moisture, oxidation, and contamination inside the cooling medium have consequences far beyond electrical breakdown. Poor heat removal amplifies every other aging mechanism at work inside the transformer.

Dry-type and liquid-filled contrasts

Dry-type transformers rely entirely on air movement. Their survival depends on room ventilation, airflow paths, and the absence of obstructions. Dust accumulation, blocked louvers, or stalled fans quietly undermine cooling effectiveness.

Liquid-filled designs add complexity but gain stability. Oil buffers temperature swings and distributes heat more evenly. The tradeoff is maintenance sensitivity. Oil condition, circulation paths, and radiator cleanliness all influence real cooling performance. This distinction becomes especially important when comparing pad-mounted and substation transformer installations operating under very different thermal environments.

Cooling methods in practical service

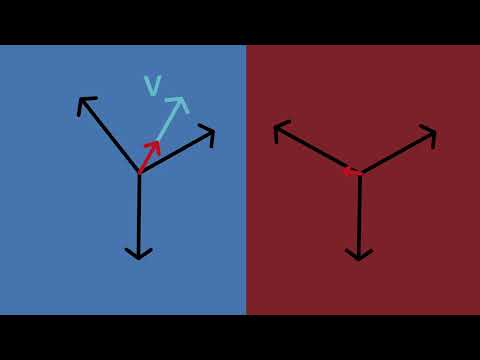

Transformer cooling designations such as ONAN, ONAF, and OFAF describe how oil and air are moved, not merely how they are labeled. In practice, the distinction matters because each method responds differently to load variability.

Natural systems favor simplicity and reliability. Forced systems favor thermal capacity. Most utility transformers operate across both regimes during their service life. The choice of cooling method is therefore part of the broader transformer design strategy rather than a secondary accessory decision.

Cooling is therefore not a fixed characteristic. It is an operating behavior.

Why oil quality still matters here

Transformer cooling efficiency depends on the liquid's physical behavior. Viscosity, moisture content, and oxidation products all change how easily oil circulates and transfers heat. This is why oil condition affects thermal control long before it threatens dielectric strength.

Routine review of transformer oil analysis results often reveals cooling degradation before electrical symptoms appear.

High-quality insulating oil slows oxidation, resists moisture absorption, and maintains predictable flow characteristics over time. When oil degrades, cooling performance declines as well, even if electrical tests remain acceptable.

Synthetic and legacy fluids

Modern indoor installations often rely on less-flammable or nonflammable liquids to reduce fire risk. Older transformers may still contain askarel-based fluids, which require special handling due to environmental and health concerns. While those fluids provided excellent thermal behavior, their regulatory burden now outweighs their technical benefits.

Fluid selection, therefore, must consider both cooling performance and the material behavior described in the characteristics of dielectric fluid under operating stress.

Transformer cooling design must always be evaluated alongside safety, environmental compliance, and service accessibility.

Why transformer cooling affects more than temperature

Uneven cooling creates uneven aging. Windings exposed to persistent hot spots lose mechanical strength faster. Paper near those regions embrittle. Oil in those paths oxidizes more rapidly. Over time, thermal imbalance becomes structural imbalance.

Sign Up for Electricity Forum’s Utility Transformers Newsletter

Stay informed with our FREE Utility Transformers Newsletter — get the latest news, breakthrough technologies, and expert insights, delivered straight to your inbox.

In that sense, cooling defines the operating environment in which all other transformer behaviors occur, including the gas patterns later interpreted through dissolved gas analysis.

This is why cooling is not only about average temperature. It is about temperature distribution.

Transformer Cooling as a diagnostic boundary

Cooling does not diagnose faults. It shapes how faults develop. Poor cooling accelerates every degradation mechanism, making later diagnostic interpretation more difficult and less predictable.

In that sense, cooling defines the operating environment in which all other transformer behaviors occur.

That is why serious transformer programs treat cooling not as a maintenance checklist item, but as a life-governing system.

Related Articles