General Electrical Safety Procedures

By Frank Baker, Associate Editor

NFPA 70E Training

Our customized live online or in‑person group training can be delivered to your staff at your location.

- Live Online

- 6 hours Instructor-led

- Group Training Available

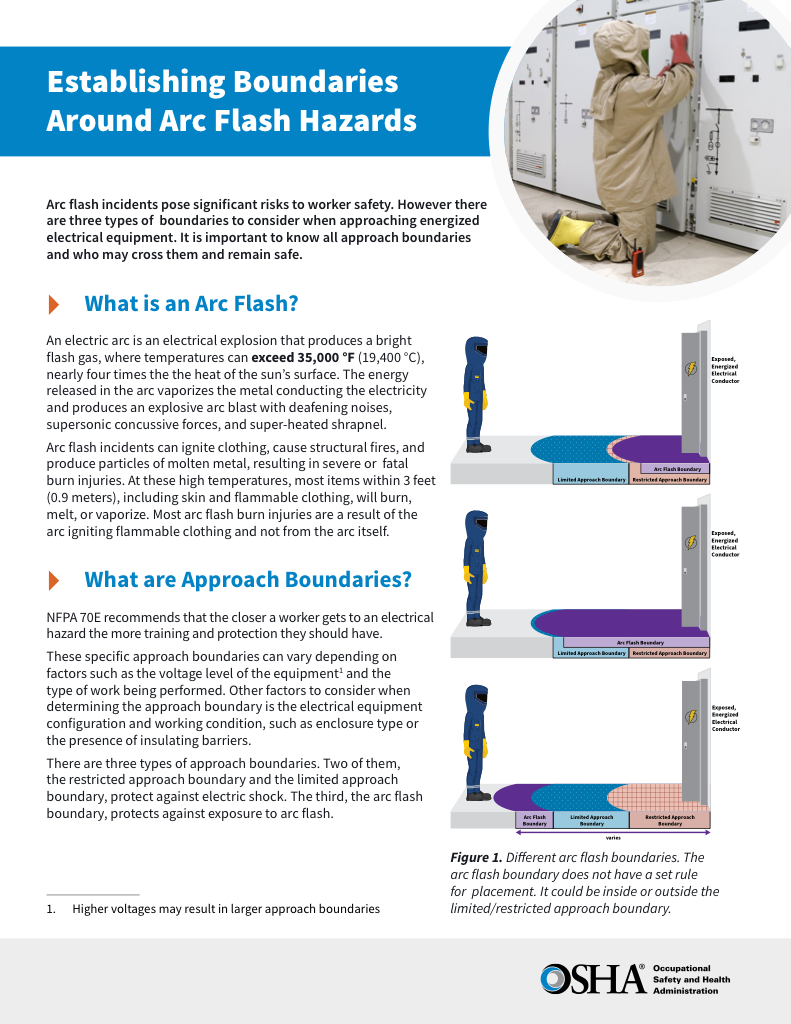

Download Our OSHA 4474 Fact Sheet – Establishing Boundaries Around Arc Flash Hazards

- Understand the difference between arc flash and electric shock boundaries

- Learn who may cross each boundary and under what conditions

- Apply voltage-based rules for safer approach distances

General electrical safety reduces arc flash and shock risk by de-energizing, locking out, verifying the absence of voltage, and using task-based PPE. It fits real industrial work, where mislabeled sources, backfeed, and rushed testing cause incidents.

General Electrical Safety Explained

In industrial and commercial facilities, “general electrical safety” is not a poster or a toolbox talk. It is the ordinary discipline that keeps routine tasks from turning into emergencies. The goal is simple: keep people away from energized parts whenever possible, and when you cannot, control exposure so tightly that improvisation is not part of the plan.

This page is written for workplace conditions, not weekend DIY. The same physics applies in a home, but the risk profile differs on plant, data centre, warehouse, hospital, and multi-trade job sites. You have more equipment, more hands, more switching, more temporary power, and more ways for one small mistake to reach someone who never saw it coming.

If you need the broader context that sits behind the examples here, start with the main Arc Flash hub and then come back to this page with those concepts in mind.

Basic Electrical Safety

Basic electrical safety starts with treating every electrical circuit as if it can hurt you, because in real workplaces and on real sites, electrical hazards rarely announce themselves. Before you touch electrical equipment, take a second to look for the things that actually injure people: damaged power cords, crushed extension cords, missing grounding pins, wet areas, and tools and equipment that have been “temporarily” repaired too many times.

Test Your Knowledge About Arc Flash!

Think you know Arc Flash? Take our quick, interactive quiz and test your knowledge in minutes.

- Instantly see your results and score

- Identify strengths and areas for improvement

- Challenge yourself on real-world electrical topics

Double-insulated power tools reduce risk, but they do not make unsafe conditions acceptable, especially where a ground fault is possible. Stay alert around overhead lines, keep cord sets out of pinch points and water, and stop using any tool that feels hot, smells odd, trips protection, or gives even a hint of electrical shock.

If an incident happens, the priorities are clear and they are not technical. Do not grab someone who may still be energized, break contact with the source if you can do so safely, and call 911 immediately. After the scene is safe, the next step is not guesswork, it is bringing in a qualified electrician to find the cause, confirm what is properly grounded, and correct the condition before work resumes.

In many cases the root issue is not dramatic, it is ordinary: a compromised cord, a miswired receptacle, an overloaded circuit, or a missing protective device that would have cleared a fault quickly. The safest crews develop the habit of treating electrical safety as part of the job setup, not something to think about only after a close call.

Poor Decision Making

Most incidents trace back to a few decisions made too quickly or not made at all.

First, decide whether energized work is truly justified. If the task can be planned so the circuit is de-energized, isolated, and verified, that is usually the safest starting point.

Second, decide who is actually qualified for the work as performed today, not on paper. A worker can be competent yet unprepared for a specific configuration, especially when drawings are outdated or labels are optimistic, which is exactly why the definition of a qualified electrical worker matters in the real world.

Third, decide how you will control shock risk before you think about gloves. Approach distance, barriers, guarded conductors, and the condition of tools matter. PPE is not a substitute for basic control, and even experienced crews get caught when they drift inside the limited approach boundary without treating it like a hard line.

Fourth, decide what could surprise you. Backfeed from UPS systems, control power from a different source, stored energy in capacitors, induced voltage on long runs, and shared neutrals are not rare stories. They are routine in the right environment.

Fifth, decide what makes you stop. If the circuit identity is uncertain, the work area is wet, the enclosure is damaged, access is crowded, or the last test was not witnessed and repeated, the correct move is to pause and reset the plan.

What usually goes wrong in the field is not mysterious; it is familiar. A disconnect is locked out, but it's the wrong one. A panel schedule is wrong by one line. Someone “just checks” with a non-contact tester and treats that as proof. A temporary cord is pinched under a door for a week, and nobody notices the insulation damage until it is too late. A job runs long, the crew changes, and the boundary that was understood in the morning becomes an assumption by mid-afternoon. None of that reads like a dramatic accident report while it is happening. That is exactly why it is dangerous.

If you want a reality check on why “good intentions” still fail, the patterns in 10 most common errors in arc flash analysis map closely to the same rushed assumptions that show up in everyday electrical work.

Electricity Today T&D Magazine Subscribe for FREE

- Timely insights from industry experts

- Practical solutions T&D engineers

- Free access to every issue

Understanding Electricity

Electricity does not need intent to hurt you. It only needs a path. The moment a person becomes the easiest route between energized conductors and ground, or between two conductors, the body becomes part of the circuit. That can mean a mild shock or a fatal event. The difference is often a handful of variables that people do not feel in advance: contact area, moisture, clothing, footwear, the surface underfoot, and how long the contact lasts.

In practice, most workplace electrical incidents fall into two buckets. The first is shock, where current passes through the body. The second is thermal and pressure injury from an arc event, where the energy is released violently through air. Arc flash is heat and light. Arc blast is force. Both can occur together, and both can be triggered by ordinary actions when the equipment's condition, configuration, or work method is incorrect.

For crews who hear those terms used interchangeably, it helps to keep the distinction clear in arc flash vs arc blast, because the controls and injuries are not the same even when the initiating fault is.

If you have ever opened an enclosure and seen scorching, loose terminations, damaged insulation, missing blanks, or evidence of water ingress, you have already seen why “normal operation” is not a guarantee of safety. Equipment can run while quietly drifting toward failure. That is why controls cannot rely on optimism.

Static electricity shows up as nuisance shocks and can ignite certain atmospheres. Still, the electrical safety decisions that matter day to day in facilities are driven by current flow, fault current, and the conditions that allow an arc to start and sustain. The dangerous moment is often the simplest one: the first contact, the first probe, the first slip, the first time a tool bridges something it should not.

People also underestimate how often the system layout creates confusion. A feeder that was rerouted years ago. A spare breaker repurposed. A motor control circuit that pulls from a different panel than the power conductors. A piece of equipment with multiple sources, including control power. These are not “edge cases.” They are the normal clutter of real plants.

General Electrical Safety Practices

A serious electrical safety program does not start with PPE. It starts upstream, with the expectation that energized exposure is the exception, not the default, and that jobs are planned so the system can be placed in an electrically safe work condition whenever feasible. That planning shows up in isolation steps, lockout/tagout, verification of absence of voltage, and control of access to the work area.

Lockout/tagout is only as strong as the thinking behind it. Isolation has to match the actual sources, not the sources people assume exist. Verification must be performed with a properly rated meter: first on a known live source, then on the circuit you believe is isolated, and finally on the live source again. If that feels repetitive, it is. Repetition is cheaper than an incident.

Where facilities struggle is not the idea of lockout, it is the day-to-day discipline of doing it the same way every time, which is why a clear lockout/tagout procedure is often the difference between a controlled job and a near miss.

The verification step deserves its own respect, because “we locked it out” is not proof, and the sequence in to verify an electrically safe work condition is the part people tend to compress when the schedule is tight.

The Role of PPE

PPE belongs in the conversation, but in the right place. PPE is what you wear when the risk cannot be engineered away or administratively eliminated. It is not a permit to take shortcuts. When PPE becomes the first control people mention, it is usually a sign that the work method needs attention.

For arc flash tasks, PPE selection should feel like the last layer added after everything else has been tightened, and the practical detail in NFPA 70E PPE requirements helps keep that thinking grounded.

Inspections are another place where credibility matters. Fixed time intervals can sound authoritative, but in the real world, inspection and testing frequency should follow exposure and consequence: harsh environments, high-traffic areas, temporary power, frequent plug-in activity, maintenance history, and the condition of enclosures and cord sets. If equipment lives in a wet process area, is moved weekly, or is impacted by carts and materials, “periodic” needs to mean “often.” If equipment is stable, enclosed, well-managed, and rarely disturbed, a different cadence can be justified. What matters is that the rationale is clear and the follow-through is consistent.

If you want a quick, practical tool that works on real sites, use a short pre-task brief before any job that involves opening covers, testing, or approaching energized parts. It takes less than a minute when a crew is used to it:

- What are we touching, and what is the exact source?

- How will we isolate it, and who controls the lock?

- How will we verify it is dead, and who will witness the test?

- What is the arc flash and shock exposure for this task?

- What changes would make us stop and reset the plan?

That is not theatre. It is how you catch the quiet errors: the mislabeled disconnect, the second source, the missing barrier, the rushed assumption.

General electrical safety also depends on small habits that do not look heroic. Keep covers and blanks in place. Keep access clear. Keep cords out of pinch points and away from heat. Treat damaged insulation and loose fittings as urgent, not cosmetic. Maintain GFCI protection where it is required and where conditions make it a sensible control. And when a worker says something feels off, treat that as data, not a delay.

Related Article