SCADA Architecture

By Frank Baker, Associate Editor

Download Our OSHA 3875 Fact Sheet – Electrical PPE for Power Industry Workers

- Follow rules for rubber gloves, arc-rated PPE, and inspection procedures

- Learn employer obligations for testing, certification, and training

- Protect workers from arc flash and electrical shock injuries

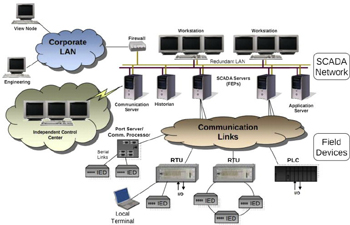

SCADA architecture describes how field devices, control networks, and supervisory software are organized to monitor, automate, and manage industrial and utility systems, supporting real-time visibility, reliable communication, and coordinated control.

SCADA Architecture – System Design

Supervisory control and data acquisition systems do not succeed or fail on software alone. Their reliability is shaped by how sensors, controllers, communication paths, and operator tools are arranged into a coherent structure. SCADA architecture is the framework that enables this coordination, especially in environments where equipment is geographically dispersed, and operational decisions must be made quickly and with confidence.

In practice, architecture decisions determine how efficiently data moves from the field to the control room and how effectively operators can respond to changing conditions. A well-considered design supports stable data acquisition, predictable system behavior, and visibility that extends beyond alarms into meaningful operational insight. Utilities and industrial operators rely on this structure to manage assets that cannot be manually supervised in real time.

Rather than existing as a single fixed model, SCADA Architecture reflects a series of design choices shaped by geography, risk tolerance, communications infrastructure, and operational priorities. Those choices explain why electrical utilities, water systems, pipelines, and large industrial facilities often deploy different architectures even when using similar technologies.

For a broader foundation, readers who want a conceptual overview can refer to the companion article on What is SCADA is and how it evolved.

Core Layers of SCADA Architecture

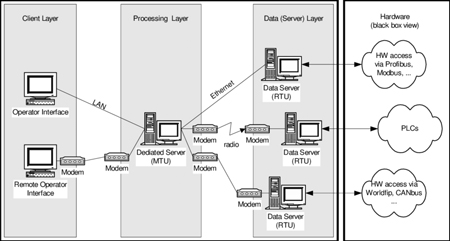

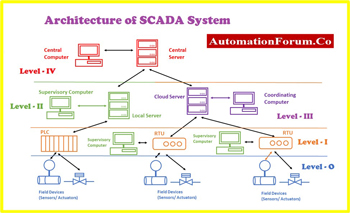

Most SCADA environments share a layered structure, but the boundaries between layers are not always rigid in real deployments. At the outer edge of the system, field instrumentation captures physical conditions such as voltage, current, pressure, temperature, or flow. These measurements form the raw input that drives every higher-level function.

Sign Up for Electricity Forum’s Smart Grid Newsletter

Stay informed with our FREE Smart Grid Newsletter — get the latest news, breakthrough technologies, and expert insights, delivered straight to your inbox.

Closer to the process, programmable logic controllers and remote terminal units translate sensor signals into action. They execute local logic, manage interlocks, and continue operating even if communications to the control center are temporarily lost. In electrical applications, this local autonomy is essential for maintaining safety and stability during disturbances. SCADA architecture plays a central role in how utilities coordinate automation across assets, especially when layered with coordinated automation schemes that manage protection, control, and response at scale.

Above the control layer sits the supervisory environment, where field data is consolidated, contextualized, and presented to operators. The strength of this structure lies in its continuity. Conditions in the field are observed, interpreted, and acted upon without requiring constant human intervention, yet operators retain the ability to intervene when judgment is required.

A more detailed walkthrough of this interaction is covered in the article How Does SCADA Work in Practice.

Communication and Data Flow

The value of any SCADA system depends heavily on how information moves through it. Communication networks form the connective tissue between remote assets and centralized control, often spanning long distances and operating under challenging environmental conditions. As grid complexity increases, SCADA systems must integrate securely with broader modernization efforts, including evolving approaches to grid cybersecurity strategy that address both operational technology and enterprise risk.

In the field, communication choices are shaped by terrain, latency tolerance, and reliability requirements. Fibre networks may be preferred in substations, while radio or cellular links are common in remote or mobile installations. Protocol selection plays an equally important role. Standards such as Modbus, DNP3, and IEC 60870 persist because they balance efficiency with resilience, not because they are fashionable.

Beyond real-time control, the communication infrastructure also supports historical data collection. That data underpins trending, fault analysis, and maintenance planning, making communication reliability as important for long-term asset management as it is for immediate control actions. The way data flows through a SCADA environment is closely tied to advances in smart grid communication, where latency, redundancy, and protocol selection directly affect system reliability.

SCADA in Industry

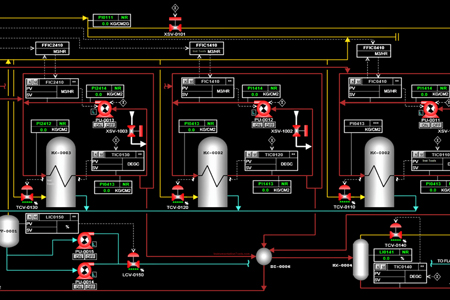

In industrial environments, a control system quietly manages thousands of signals as it collects data from sensors, meters, and field devices, turning raw measurements into actionable insight. This gathering data process feeds into supervisory control and data acquisition SCADA platforms, where monitoring and control occur across wide areas using SCADA networks.

At the field level, programmable logic controllers PLCs and remote terminal units RTUs handle real-time control processes, executing logic written in a specialized programming language to respond instantly to changing conditions. Operators interact with this complex infrastructure through a human-machine interface HMI, which translates system status into readable screens and alarms, allowing people to oversee operations without being physically present at every asset.

SCADA Software and User Interfaces

At the supervisory level, SCADA software provides the environment where raw data becomes operational awareness. This layer evaluates incoming signals, applies logic, generates alarms, and stores historical records that help engineers understand how systems behave over time.

Human-machine interfaces translate this activity into visual form. Effective HMI design does not overwhelm operators with data. Instead, it presents status, trends, and alarms in a way that reflects how people actually think and respond under pressure. In high-voltage environments, clarity and restraint in screen design can be as important as the accuracy of the data itself. At the operator level, effective visualization remains critical, which is why SCADA software design is often closely aligned with best practices in SCADA HMI development.

FREE EF Electrical Training Catalog

Download our FREE Electrical Training Catalog and explore a full range of expert-led electrical training courses.

- Live online and in-person courses available

- Real-time instruction with Q&A from industry experts

- Flexible scheduling for your convenience

Operators continuously interact with SCADA systems, adjusting setpoints, acknowledging alarms, and responding to abnormal conditions. The usability of the interface directly affects response time, decision quality, and ultimately system safety.

Types of SCADA System Architecture

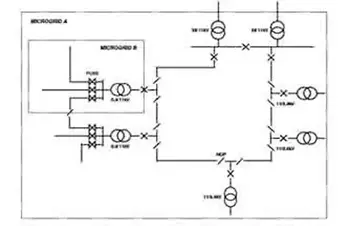

SCADA architecture has evolved alongside advances in computing and communications. Early monolithic systems relied on centralized hardware with limited external connectivity. While simple, these designs offered little flexibility and were vulnerable to single points of failure.

Distributed architectures introduced resilience by spreading processing tasks across multiple machines. This shift improved reliability and allowed systems to scale as operational needs grew. Networked architectures later became the dominant model, integrating all components through standardized communications and shared data environments.

Modern implementations extend these ideas further, incorporating cloud platforms, mobile access, and analytics tools. While the underlying principles remain familiar, the emphasis has shifted toward integration, scalability, and secure remote access rather than purely centralized control.

Applications in Electrical Automation

In electrical systems, SCADA underpins much of modern grid operation. Transmission lines, substations, and switchgear are continuously monitored, allowing operators to detect abnormalities before they escalate into outages or equipment damage.

PLCs control breakers, transformers, and voltage regulation equipment, while SCADA software provides the situational awareness needed to balance load, manage faults, and coordinate maintenance. Data collected across the system supports both real-time operations and long-term planning, reducing manual intervention and improving response consistency.

As smart grid initiatives expand, SCADA increasingly functions as the coordination layer that connects traditional infrastructure with distributed energy resources and advanced control strategies. In substations, SCADA supports real-time visibility and control, forming the backbone of substation SCADA systems used for protection, monitoring, and switching operations.

The Role of System Integrators

Behind every effective SCADA deployment is careful integration work. System integrators translate operational requirements into functioning systems by configuring communications, programming control logic, and shaping user interfaces around how operators actually work.

Their role extends beyond installation. Integrators tune alarm strategies, validate data flows, and ensure that hardware and software components behave as a unified system rather than isolated parts. In regulated industries, this work must also align with performance expectations and safety practices specific to the application.

A well-integrated architecture becomes more than a technical diagram. It becomes the operational backbone of critical infrastructure, supporting informed decision-making, minimizing downtime, and enabling coordinated control across complex, distributed systems.

Related Articles